|

| Nikon Coolpix P1500 |

about the banner…

Water lilies at the Brooklyn Botanical Garden Orchid Show, April 5, 2014. Taken with the Nikon D610 + AF-S Zoom NIKKOR 24-85mm f/3.5-4.5 G ED VR. 1/600 s @ f/5.6 -0.67, ISO 800.

Wednesday, November 30, 2011

ATG Updates

I decided to rearrange things a bit. With the ongoing posting of Post-Processing tutorials, I decided to change the “Retouching” tab to “Tutorials” and include both Photography and Post-Processing. “Tips and Tricks” remains, and it now devoted exclusively to quick solutions and how to’s.

Labels:

What’s New

Monday, November 28, 2011

Color Enhancement with L*a*b* Curves

If you want to enhance color, I mean really enhance color, L*a*b* is the way to do it.

If you want to enhance color, I mean really enhance color, L*a*b* is the way to do it.The L*a*b* color space processes color in the same way the human eye does…separate from luminosity. Highly sensitive photoreceptors in the human eye called rods do not respond to color, while the less sensitive photoreceptors called cones do. The number of cones is only about 5% of the rods, but they come in three different types which respond to…you guessed it…red, green and blue wavelengths.

In low light, the rods enable us to see in the dark, at the expense of color perception. Under normal light, the cones take over to add the other dimension of vision: color. The three “axes” of color, red, green and blue, are gathered by the cones and processed by a secondary layer of the retina which converts these colors into two opposing-color channels, representing four axes of color: green/magenta and blue/yellow. It’s this color model after which the L*a*b* color space was conceived.

Because the L*a*b* color space separates Luminosity (L) from color (a, b) you can process color separately, maintaining the delicate tonal relationships. However, you can also change the lightness of the image without diminishing the color.

As you attempt to enhance color in an RGB image, you also affect the luminosity, which is encoded in each of the three color channels. In an L*a*b* image, you can process green and magenta (a channel) and blue and yellow (b channel) separately from the luminosity information (Lightness channel), and this capability can achieve some amazing results.

Take this image for example. It has some amazing colors, but they’re extremely muted:

In order to make this image come alive, we need to add contrast, and we need to separate the reds from the greens, and the greens from the yellows. We can process the color and contrast separately using curves in the L*a*b* color space.

The easiest and most convenient way to do this is in a single image file, using Smart Objects.

1. Open the image, select the background layer and duplicate it (Command+J)…

2. Convert the layer to a Smart Object…

3. Double-click the Smart Object layer to open it into a new window. It will open as a .psb image (Photoshop Large Document Format), which is stored inside the original image.

4. Next, convert this image to the L*a*b* color space…

5. Add a Curves adjustment layer. You can rename it “Luminosity” or “Contrast” if you wish.

6. Now, let’s set up the Auto Options for curves. Click on the Adjustment Panel’s options menu icon…

7. Enter these shadow and highlight clipping values, check the “Save as defaults” box, and click OK.

8. The endpoints of the curve will now be mapped to the black and white points of the image, maximizing contrast. You can now adjust the curve for the most pleasing balance of contrast vs. brightness.

In this case, I’ve set the 35% point back to 35, adjusting the gamma and reducing the washed-out effect. The resulting image looks like this:

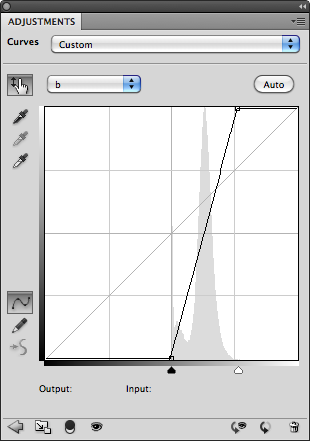

9. Now comes the magic. Add a second curve as in Step 5, select the a channel, and click the Auto button. repeat for the b channel. You can rename this curve “Color” or “Saturation” if you wish.

What you wind up with is an image in which the absolute maximum amount of color separation has been extracted…

And when the Curve Layer’s opacity is adjusted to yield a more realistic level of color, say 35%…

…The image comes alive. Compare this with the image at the top of the page. You can now press Command+S to save the changes, and Command+W to close the .psb document window, returning you to the main window. The L*a*b* image is now embedded within the RGB image, and converted back to its space automatically. Be sure to also save the RGB image, or the changes will be lost.

Now, turn the L*a*b* layer’s visibility on and off to see the difference. You don’t have to duplicate the background layer to apply this effect, but we’ve done it here so you can easily see the difference L*a*b* curves have made.

Now, what we’ve done here is maximized the color separation between the greens and the magentas and the blues and the yellows. However, not all images have the same proportions of these colors, and the result of using this technique is that neutral colors will no longer be neutral. It’s not a major problem in this image, but it may be in others. Let’s go back to the a and b curves to see why.

The Auto function has mapped the curve the color information in the image. As a result it is no longer symmetrical. In order for neutral colors to remain neutral, the curve must be symmetrical and pass through the origin at 0, 0. If we adjust the curves manually to look like this, we can restore neutrality…

The shadows no longer have a bluish cast, and if there were any white highlights, they would have remained white. But the separation between the reds and the greens is not nearly as dynamic.

But there is a way that we can have our cake and eat it too.

In this image at least, there are no neutrals grays, so we can “filter” the L*a*b* curve out of the highlights and shadows of the “auto” curve using the layer’s Blending Options.

1. Control or Right-click on the space next to the curve’s label to open up the layer’s Blending Options dialog…

2. Now, holding down the Option key, separate the handle of the Underlying Layer “Blend If” shadow slider and drag it to the right until neutrality is restored to the shadows. Repeat for the highlight slider, dragging it to the left.

And the resulting image…

…transformed from this…

If we had performed a similar adjustment in RGB under the best conditions (a contrast curve in Luminosity mode and Hue/Saturation in Color mode) this would have been the result…

I would describe this as largely monochromatic with little separation of color. This is important, because it’s exactly this type of image on which L*a*b* can truly work its magic. Without separation of color, tools like Selective Color cannot work effectively.

Normal images however can also benefit from L*a*b* processing. Take for example this photo of a little house, titled appropriately “Little House” in Boothbay Harbor, Maine:

It has a relatively normal balance of color, and so it’s histogram in the a and b channels is fairly centered about the origin, where neutrality occurs.

In this case, we can place a point in the center of the curve, and move it to the origin (0,0), which restores the original color balance, returning neutrality to the whites, grays and blacks. However, this creates an actual curve, which will accentuate some colors more than others, and which may not be desirable. If this is the case, we can place two additional points along the curve close to the origin to straighten it out…

And this is the end result:

Compared to the original…

Keep in mind that if you do perform this on a separate layer, you can brush the effect in, or use masking to make a local adjustment. With greater separation of colors, tools like Selective Color and Hue/Saturation work better. For example, the greens in this image are a little on the blue side for my taste, so I can use Hue/Saturation in the L*a*b* space to target the greens and tone them down a bit…

That’s better. I could also have used Selective Color on the RGB side, but unfortunately this adjustment layer is not available in the L*a*b* color space. However, it works to your advantage to make color adjustment in the L*a*b* space where possible, since its unlimited color gamut will produce better results.

Here are some other important things to know about the L*a*b* color space:

- You can freely convert back and forth between RGB and L*a*b* without any loss or change in color balance.

- Because luminosity and color are handled separately, it’s possible to create colors that cannot possibly exist in nature, such as a fully saturated white or black.

- When “impossible” colors are converted back to the RGB color space, colors are created that did not exist in the original image.

- By converting a small-gamut color space such as sRGB to a larger gamut space such as AdobeRGB or ProPhoto before applying L*a*b* color enhancement, it’s possible to restore some of the color vibrancy not captured when the image was taken.

Help for sRGB Images

The sRGB color space was designed to accommodate a large number to devices, and so it has a limited color gamut. This makes it difficult to use as a working color space and still obtain good results. But it’s even worse as a capture space, because it doesn’t give you all the colors in the original scene in the first place. L*a*b* can help to restore vibrancy to these images by producing colors that do not exist in the original capture, and converting them back to the destination space.

This photo was taken with a Canon PowerShot SD780 IS, which can only record images in the sRGB color space. The reds were stunning against the green background, rich and vivid. But when I viewed the image on my workstation, it came up short.

The reds were too magenta and saturated, and any attempt to sway them more toward yellow as they needed to be resulted in lost shape and washed-out color.

In the L*a*b* color space, I used Hue/Saturation to target the reds, slightly desaturate them, and add more yellow. This restored the shape and gave me the hue I visualized in the original scene. I then added an a/b curve to restore the saturation lost in the first step without compromising the shape. This also added vibrancy to the greens and the blue of the sky reflected in the water. This is the result:

It’s a subtle change, but much more faithful to the original image. Even though both of these images now exist in the sRGB color space, the enhancements, when converted from the unlimited gamut of L*a*b* to the limited gamut of sRBG, are very much present.

Labels:

Tutorials

Saturday, November 26, 2011

Descreening an Image

There may be times when you are required to remove the halftone “rosette” pattern from images that have been scanned from printed media. This is done to prevent the previous dot pattern from interfering with the new pattern that will be generated when the new separations are made. Another important reason to do this is to reduce file size and to restore a photographic look to the image.

When performing this process for printing, it’s assumed that you have permission to reproduce the image from its copyright holder. It may simply be a case where the original is lost or extremely difficult to obtain. The same conditions apply if you were to use the image as part of a photo composition, although copyright laws do allow images to be used without permission as long as they don’t exceed a certain percentage of the entire image.

That said, this tutorial explains how to convert the rosette pattern into a random pattern that resembles film grain with a minimal loss of detail.

Many are under the false impression that the way to do this is through blurring. Unless the image is blurred to the degree that fine detail is lost, it simply softens the existing pattern. What we need to do is to “break up” the pattern so that it’s no longer a regularly occuring texture. And the filter that excels at this is Diffuse.

Diffuse works by randomly moving pixels within each “sample”, which is exactly what we need to do to rearrange the rosette pattern to look irregular, similar to film grain. The trick is to find the optimum resolution at which to apply the filter to break up the pattern while preserving the detail.

We then apply Add Noise to enhance the effect of the Diffuse filter. Usually, 3% of uniform noise works well. Applying it as “Monochromatic” helps to keep down color noise.

To take the edge of the resulting “sharp” pixel texture, we then apply Gaussian Blur at a very low percentage, about 0.5%.

All of this results in texture similar to film grain. And since film grain is often perceived as noise, we can treat it as such and reduce it with Median, so this is the final filter we will apply. A radius of one pixel usually does the trick, as we don’t want to obscure too much detail.

Step by Step:

1. Begin with a pre-screened image (this is a crop of the original image at its orginal resolution.)

2. Assuming it was scanned at 100%, and that it has the typical line screen frequency of 133 lpi, resample the image to about 150% of its original size using Image > Image Size… (Command + Option + I). Some experimentation may be necessary to find the optimal resolution, but applying this effect to the original image often results in a substantial loss of detail.

3. This effect is best applied as a “Smart Filter” so that it’s possible to experiment with different filter values to obtain the optimum effect. To do this, convert the current layer into a “Smart Object”:

4. Apply Filter > Stylize > Diffuse…

5. Apply Filter > Noise > Add Noise…

6. Apply Filter > Noise > Median…

7. Finally, downsample the image to its original resolution (66.66… %), or the size and resolution of your choice. Your Layers panel should now look like this…

And the resulting image like this…

If the image had been simply blurred enough to obscure the rosette pattern, it would have looked like this:

Moving Forward, you can now apply noise reduction to smooth out the grain if desired. Another trick is to increase the Median filter slightly (2 to 3 pixels is usually a good value) and apply Unsharp Mask to sharpen the image. The result may not be to your liking, but it is an option if the grain is distracting.

When performing this process for printing, it’s assumed that you have permission to reproduce the image from its copyright holder. It may simply be a case where the original is lost or extremely difficult to obtain. The same conditions apply if you were to use the image as part of a photo composition, although copyright laws do allow images to be used without permission as long as they don’t exceed a certain percentage of the entire image.

That said, this tutorial explains how to convert the rosette pattern into a random pattern that resembles film grain with a minimal loss of detail.

Many are under the false impression that the way to do this is through blurring. Unless the image is blurred to the degree that fine detail is lost, it simply softens the existing pattern. What we need to do is to “break up” the pattern so that it’s no longer a regularly occuring texture. And the filter that excels at this is Diffuse.

Diffuse works by randomly moving pixels within each “sample”, which is exactly what we need to do to rearrange the rosette pattern to look irregular, similar to film grain. The trick is to find the optimum resolution at which to apply the filter to break up the pattern while preserving the detail.

We then apply Add Noise to enhance the effect of the Diffuse filter. Usually, 3% of uniform noise works well. Applying it as “Monochromatic” helps to keep down color noise.

To take the edge of the resulting “sharp” pixel texture, we then apply Gaussian Blur at a very low percentage, about 0.5%.

All of this results in texture similar to film grain. And since film grain is often perceived as noise, we can treat it as such and reduce it with Median, so this is the final filter we will apply. A radius of one pixel usually does the trick, as we don’t want to obscure too much detail.

Step by Step:

1. Begin with a pre-screened image (this is a crop of the original image at its orginal resolution.)

2. Assuming it was scanned at 100%, and that it has the typical line screen frequency of 133 lpi, resample the image to about 150% of its original size using Image > Image Size… (Command + Option + I). Some experimentation may be necessary to find the optimal resolution, but applying this effect to the original image often results in a substantial loss of detail.

7. Finally, downsample the image to its original resolution (66.66… %), or the size and resolution of your choice. Your Layers panel should now look like this…

And the resulting image like this…

If the image had been simply blurred enough to obscure the rosette pattern, it would have looked like this:

Moving Forward, you can now apply noise reduction to smooth out the grain if desired. Another trick is to increase the Median filter slightly (2 to 3 pixels is usually a good value) and apply Unsharp Mask to sharpen the image. The result may not be to your liking, but it is an option if the grain is distracting.

Labels:

Tutorials

Monday, November 21, 2011

Samyang 35mm f/1.4 Aspherical UMC

Another extraordinary lens from Samyang…

Marketed in the US under the Rokinon brand name, this is the latest addition to an expanding line of manual-focus lenses by the Korean manufacturer Samyang. It retails for about $549.00.

|

| Samyang/Rokinon 35mm f/1.4 AS UMC for Nikon |

Labels:

Samyang 35mm f/1.4 AS UMC,

What’s New

Saturday, November 19, 2011

Quest for the Digital Rangefinder, Part III

My quest may soon be over. And Fujifilm may be my next serious camera.

Of course by rangefinder I mean “rangefinder style” since the Leica M9 is the only true digital rangefinder, and this technology is somewhat misplaced in the digital domain. Ever since the debut of the Finepix X100, it’s clear that Fujifilm gets the whole rangefinder thing. The X10 is only further proof, with all the look and feel of a rangefinder in a fixed-lens zoom. But next year something will happen that will seal the deal: Fujifilm’s interchangeable-lens hybrid viewfinder masterpiece.

It was leaked a few days ago that the successor to Fujifilm’s successful X100 will have interchangeable lenses and an organic APS-C sensor which is claimed to have better performance than the typical full-frame sensor. And, if they keep the hybrid viewfinder, this will truly be the camera of choice for rangefinder aficionados next to the M9.

Brace yourself: it’s probably not going to be cheap. In fact, I'’ve already committed myself to the X10 as a possible backup plan. That camera will easily quell my rangefinder desires, in a smaller, more convenient package, with all the focal lengths I’ll need with me at all times.

But just imagine; this could be the new Contax. The ultimate photographer’s camera. The universal body.

If Fujifilm’s new mount is done right, adapters will undoubtedly be available to fit M-Mount lenses. But don’t count on it. If the X10’s proprietary 39.5mm filter threads are any indication, Fujifilm wants you to stay close to the family. Still, Fujifilm’s lenses will undoubtedly be up to the task. Again the X10 proves that with its best in class 28-112mm f/2-2.8 zoom.

Of course by rangefinder I mean “rangefinder style” since the Leica M9 is the only true digital rangefinder, and this technology is somewhat misplaced in the digital domain. Ever since the debut of the Finepix X100, it’s clear that Fujifilm gets the whole rangefinder thing. The X10 is only further proof, with all the look and feel of a rangefinder in a fixed-lens zoom. But next year something will happen that will seal the deal: Fujifilm’s interchangeable-lens hybrid viewfinder masterpiece.

It was leaked a few days ago that the successor to Fujifilm’s successful X100 will have interchangeable lenses and an organic APS-C sensor which is claimed to have better performance than the typical full-frame sensor. And, if they keep the hybrid viewfinder, this will truly be the camera of choice for rangefinder aficionados next to the M9.

Brace yourself: it’s probably not going to be cheap. In fact, I'’ve already committed myself to the X10 as a possible backup plan. That camera will easily quell my rangefinder desires, in a smaller, more convenient package, with all the focal lengths I’ll need with me at all times.

But just imagine; this could be the new Contax. The ultimate photographer’s camera. The universal body.

If Fujifilm’s new mount is done right, adapters will undoubtedly be available to fit M-Mount lenses. But don’t count on it. If the X10’s proprietary 39.5mm filter threads are any indication, Fujifilm wants you to stay close to the family. Still, Fujifilm’s lenses will undoubtedly be up to the task. Again the X10 proves that with its best in class 28-112mm f/2-2.8 zoom.

Tuesday, November 15, 2011

Autumn Leaves

|

| Minolta MD 50mm f/1.7 on Nikon D90; 1/200, f/8.0, ISO 200 |

Labels:

Gallery,

Nature Photography,

Post-Processing

Monday, November 14, 2011

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)